Exploring Madness in a Post-War Age

Following the second World War it was understood that the world had gone mad, this being the only possible conclusion to the disintegration of humanity and reason of the previous five years

Who is Mad and Why?

Following the second World War it was understood that the world had gone mad, this being the only possible conclusion to the disintegration of humanity and reason of the previous five years. In a mad world, there existed ‘mad men,’ yet the definition of who and what was ‘mad’ or ‘insane’ to use the prevailing terminology of the period, was rooted in accepted concepts of sanity and normality. It is those who are the keepers of everyday sanity – they call themselves normal – who pass the judgement of insanity on those who do not accept their version of the world.

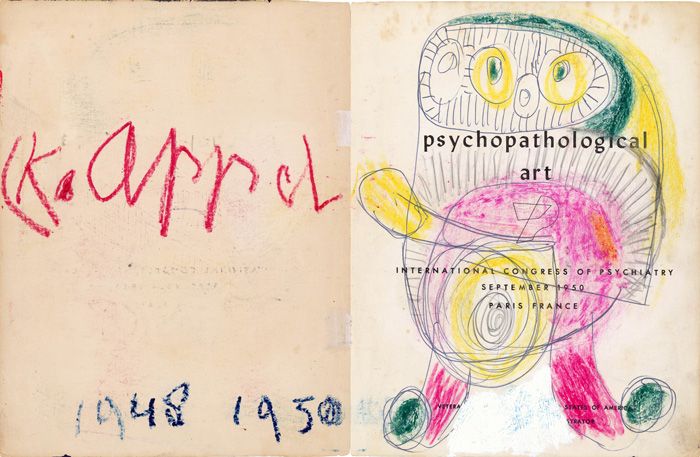

Karel Appel, The Pyschopathological Notebook

Karel Appel, The Pyschopathological NotebookWhat is the figure of insanity?

Antonin Artaud, author of The Theatre of Cruelty, described the figure of insanity, such as those that resided within the Sainte Anne Hospital, as ‘a man whom society did not want to hear and whom it wanted to prevent from uttering certain intolerable truths.’ Insane people represent the threat of another idea of the world than the one that is officially the case, and thus they are locked away in a world of their own. It is hard to sustain such an alternative vision without it corrupting and destroying your person, thus there are ostensibly always more ‘sane’ people than openly insane people, creating an imbalance of pretended power rooted in a compliant subscription to the accepted concept of normality.

Contributions by artists to liberate the ‘true soul’ of mankind over the centuries have been complicated, inasmuch as artists that have attempted to protest against the horrors of genocides, wars and extreme injustice, have also derived much of their inspiration from avant garde traditions that have thinkers such as Nietzche, Artaud at their root. There was a lust for sensation, spontaneity and compulsive expression that was not shackled to theory, the intellectualisation of the Surrealist movement was abandoned but the interest in ‘outsiders’ remained.

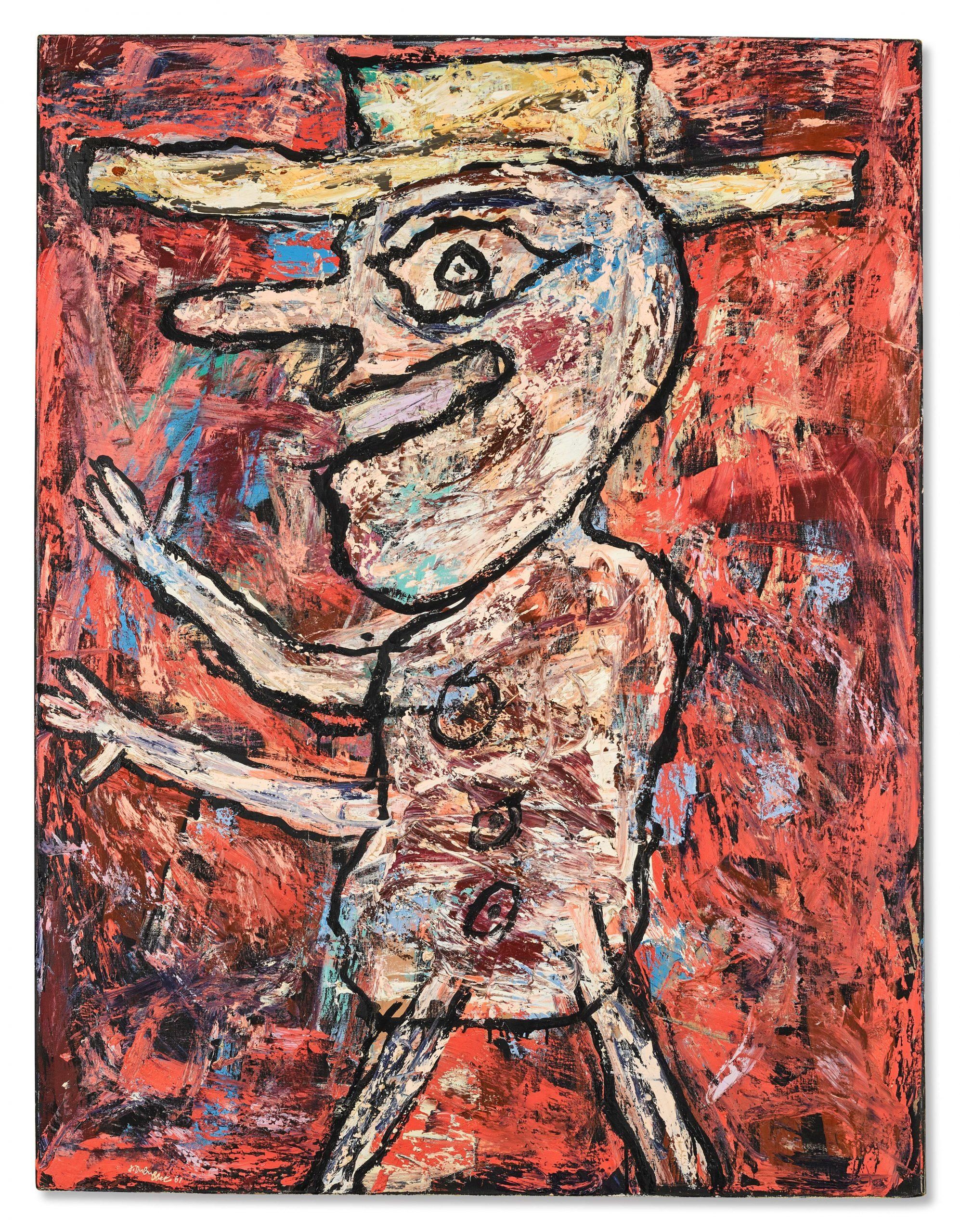

Jean Dubuffet, courtesy of Christies

Jean Dubuffet, courtesy of ChristiesThe Les Art Chez Fous exhibition was visited by every artist in Paris, a formative and ground breaking event within and outside of the art world. More than a source of aesthetic inspiration: many European artists in both the post war and pre-war periods idealised the psychotic ‘other’ as a means to advance their own values. They inhabited, to use Jean Dubuffet’s terminology, the ‘anticultural position.’

The whole argument, made most persuasively by Karl Jaspers and André Breton, that the art of the insane is “free of exterior influence and restrictions, free of calculated efforts intended to lead to profit or prestige,” depends on an assumption of the dualism between the authentic and the inauthentic. This dualism is paradoxical however as the moment a work is deemed authentic, it loses that status just as quickly.

It was the tension / relationship between the artists of Sainte Anne and mainstream culture that Dubuffet claimed resulted in a contamination and disintegration of a unique identity of the artwork produced. Michel Ragon argued that the art produced by the insane should be kept hermetically sealed, that by default the interpretation of the work resulted in a loss of any artistic quality that made it unique. Vice versa this osmosis of forms and figures from the art of the ‘insane’ into the oeuvre and dialogue of avant garde artists – such as Appel’s Notebook – generate questions surrounding artistic intention and accepted parameters of assimilation.

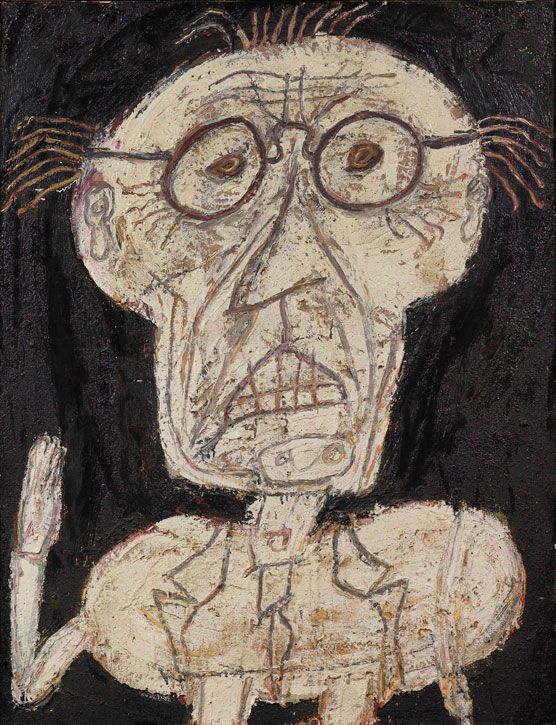

Jean Dubuffet, 1948

Jean Dubuffet, 1948Why did Western society come to idealise seemingly uncontrolled, direct expression, in whatever artistic form (primitive, childlike, naïve, insane or other label it embodies.) The intention of the art created, the intention behind the notebook, may have been rooted in a celebration of the ‘free insane mind’ yet it can also be deemed exploitative, theatrically fetishizing the vulnerable state of the exhibiting artists at the Sainte Anne exhibition.