How has 'gender' troubled art history?

Traditionally, art history has been dominated by the works of male artists, while female artists and non-binary individuals have been overlooked, omitted, and neglected.

A Brief History of Gender Binaries

Historically, gender has been simplified into binaries within the art historical canon, embedded and solidified by Western, white male theorists. This has resulted in institutionalized hierarchies within art. Traditionally, art history has been dominated by the works of male artists, supported by Kantian and Hegelian theories of aesthetic judgment and artistic genius, while female artists and non-binary individuals have been overlooked, omitted, and neglected. Due to this provenance of male dominance, the inclusion of alternative genders in art history has "troubled" both its past, present, and future. The archaic notion of art historical ‘Mothers and Fathers’ assumes a truth status regarding who can and could be part of art history, enforcing a fixed essentialist bias that requires dismantling.

Do we need a Mother or Father?

The question contemporary art historians should be asking is whether we even need a Mother or a Father. Historical accounts of gender variability are crucial at a moment when change happens at a blistering pace—current ideologies have a very short lifespan (Chiang, 2018). This essay will focus on queer theory and how its emphasis on gender as a social construct has troubled art history in several ways: through the re-reading of canonical works of art and the establishment of new critical inquiries into the future of art history.

The rightful inclusion of gender-nonconforming individuals into the canon disrupts the established status quo in a way that is insidiously viewed as even more threatening than the 20th-century push to include women in the art historical narrative. Queer theorists have not only assumed a role within the canon but have also interrogated works of art traditionally upheld as the pinnacle of artistic theory and interpretation. They subject these works to scrutiny, questioning the equation of seeing and knowing when confronted with a naked body.

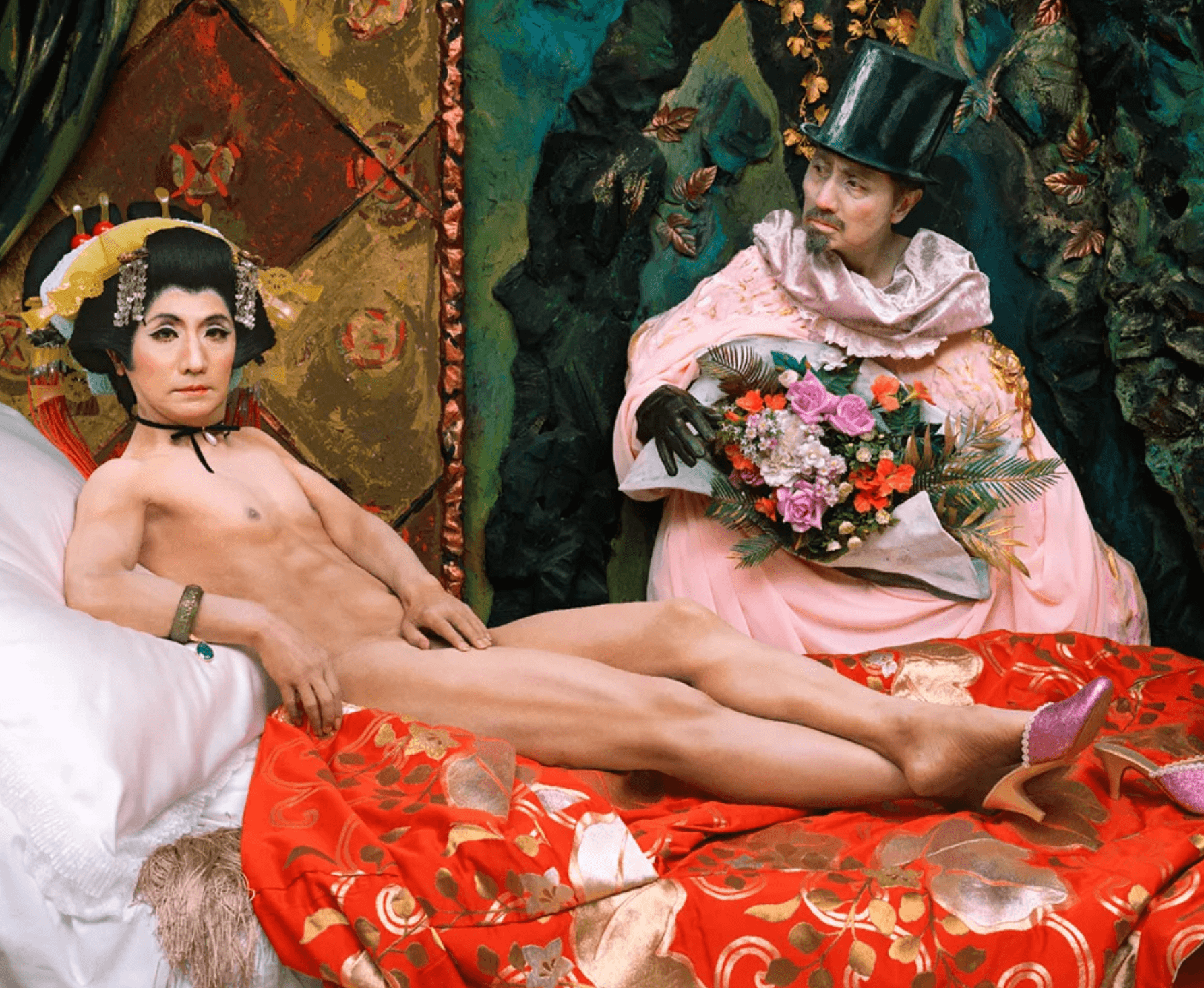

Une moderne Olympia, 2018, by Yasumasa Morimura. New York. © Yasumasa Morimura

Une moderne Olympia, 2018, by Yasumasa Morimura. New York. © Yasumasa MorimuraThis is both an ethical and methodological imperative for art history—a field that traffics in nudes as central to its defining narratives (Getsy, 2022). David Getsy exemplifies this in his dismantling of Manet’s Olympia. While the term "transgender" might be relatively new, the complexity it describes is not. Getsy highlights how the painting foregrounds the complexity of gender as an embodiment, asserting that the presence of a naked body does not directly correlate with an assigned gender. A transgender capacity is proposed through Manet’s interrogation of the nude’s status as a sign. Getsy casts a clinical spotlight on the standard of hierarchical gender binaries assumed by centuries of interpretation, including TJ Clark. Clark perceives Olympia’s gender and sex as evident in her exposed body—the idea that Olympia may be trans or intersex is dismissed, as he views Olympia as "evidently sexed." Getsy recontextualizes Manet’s work, revealing its self-reflexivity towards gender and the body, thereby disrupting and troubling traditional interpretations of the artwork.

The nude, a form so revered by the ancients, is one of the most volatile subjects in the history of art, as discussed in Getsy’s re-evaluation of Olympia. The issue lies in the casual certainty with which art history relies upon the imagery of the nude and its subsequent role in galvanizing institutional binaries. This reliance is an impossible amplification of visual attainment that presupposes a two-gendered world. Queer theory overturns this fixed narrative, challenging both feminist and traditional scholarship. By nominatively stating "it’s a boy" or "it’s a girl," we actively dictate how they should be understood rather than viewing them objectively as they appear (Hatt & Klonk, 2006).

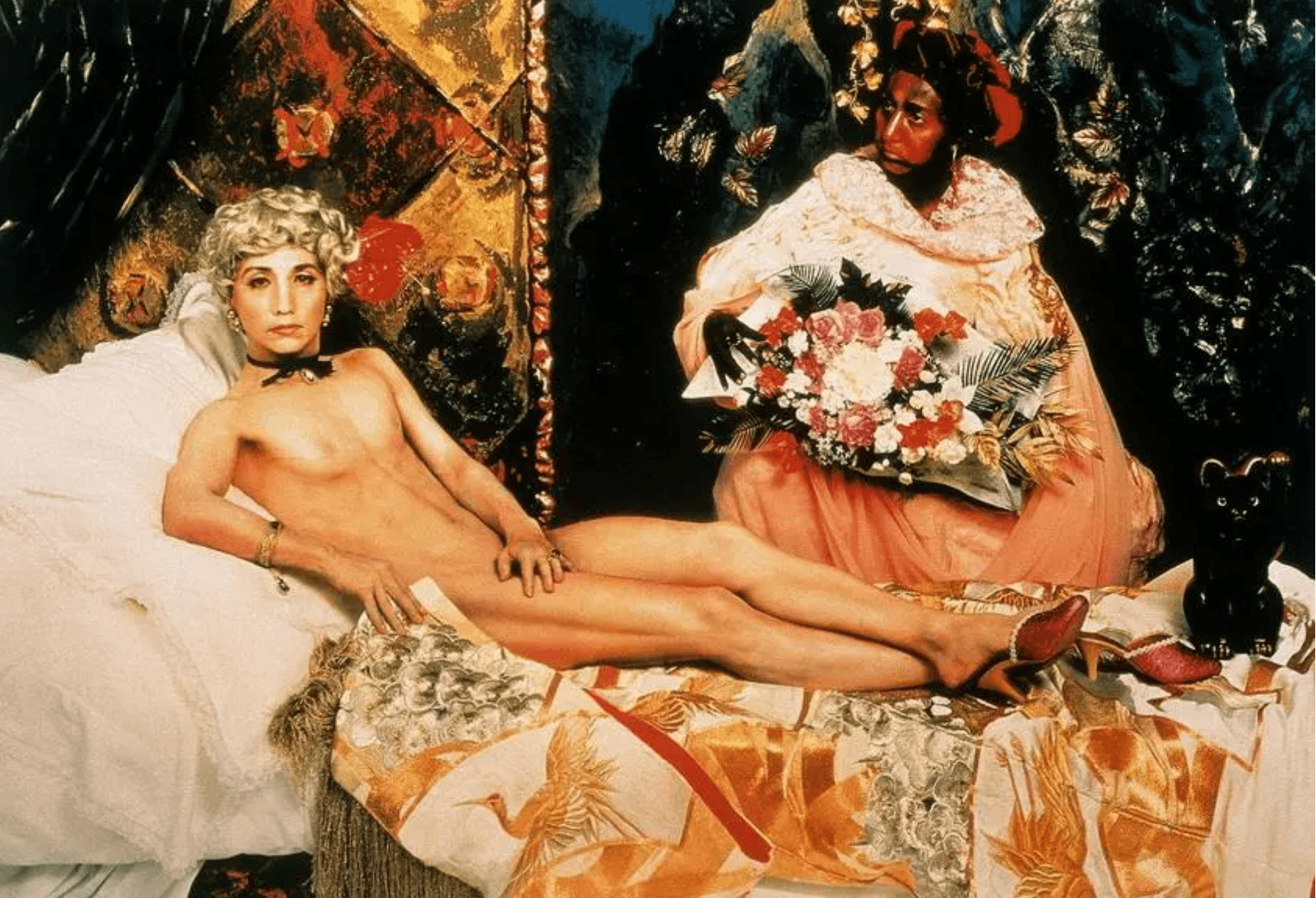

Yasumasa Morimura – Portrait (Futago), 1988.

Yasumasa Morimura – Portrait (Futago), 1988.Eliza Steinbock astutely points out that works of art and visual materials are also part of institutional apparatuses that regulate cultural production. Art history is merely attempting to situate trans people within existing binary gender regulations, reinforcing their status as nonconformists and thus troubling the field. One must understand trans representation as a radical process of reforming representational structures, concerned with "finding different visual, aural, and haptic codes through which to figure the experience of being in a body" (Halberstam, 2005). Notably absent from that definition is the word "gender."

Gender has troubled art history due to its status as an unfixed entity. Gender is not a stable attribute of identity but something that must be constantly revealed and restated (Callis, 2009). Michel Foucault, a pioneer of queer theory, argued that sexuality is a social construct, that there is nothing natural about the categories of heterosexuality and homosexuality. He introduced the notion of discourse, asserting that all concepts are historically formed and contingent, and therefore never universally true. Here, Foucault challenges Vasari and Hegel’s teleological definition of art history as driven by individual experience. He eschews continuity, instead looking for discontinuity.

Judith Butler introduced the idea of gender as performative rather than innate—that gender is something one must do throughout one’s life. Butler stated that "the cultural matrix through which gender identity has become intelligible requires that certain kinds of 'identities' cannot 'exist'—that is, those in which gender does not follow from sex and those in which the practices of desire do not 'follow' from either sex or gender" (Butler, 2004). By this decree, a masculine, woman-bodied heterosexual cannot exist as it portrays a gender that is unintelligible to the American mainstream.

In the 19th century, Vernon Lee detached femaleness from sex, and therefore from the eternal biological bind. At the time, "anything from a woman’s pen in a scholarly field would be treated with extra skepticism" (Ventrello, 2017). Within Lee’s writings, she had to express difference within a gendered system based on the binary opposition of heterosexual terms. Metaphysical language defined male and female as opposites while simultaneously masking their hierarchical relationship in the social and historical context. For Lee, subjectivity was expressed in universal terms, yet it was read as male. Women could only speak from a mediated position, and if a queer person wanted to engage in discourse, they had to use the visible conventional signs of gender to shed their invisibility (Belde, 1994).

Perhaps the time has come to do more than merely "trouble" art history, but to upend and uproot it from its ancient prejudices and fixed understandings. By discussing how gender (or the idea of it) has troubled art history, a capacity for greater insurgent agitation is revealed. Alternatively, an approach to art history that does not feel "troubled" by the notion of gender and its hazy boundaries can be incorporated. Fighting historical erasure has required the adoption of images, objects, and narratives that were not originally intended to be queer but that can repay affection and identification (Getsy, 2020).

By adopting the late Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s reparative reading approach, a more lucid and generous understanding of art history emerges. Reparative reading is fundamentally more invested in finding nourishment than identifying poison (Laing, 2022). As Sedgwick, writing as one of the many gendered mothers of art history, notes: "Because the reader has room to realize that the future may be different from the present, it is also possible for them to entertain such profoundly painful, profoundly relieving possibilities that the past could have happened differently from the way it did" (Sedgwick, 1997).