Was Russian Abstract Art Political?

The perception of abstract art as apolitical, shaped primarily by personal self-expression rather than external socio-political events is a complex and debated topic.

The Russian Avant-Garde and Politicism

The perception of abstract art as apolitical, shaped primarily by personal self-expression rather than external socio-political events is a complex and debated topic. While abstract art is often seen as a departure from explicit political messaging, it is essential to recognize that art, in any form, is inherently connected to the context in which it is created. Within early 20th C Russia, avant-gardes around the October Revolution varied with motivations in artistic expression and technique, however there were convergences surrounding belief in progress and a future of art and its theories. New forms of art had similar aesthetic concerns and technological enthusiasm that would serve for a new function in society. Multiplicity of artistic practice was compressed into a decade, artistic movements and groups catalyzing each other - Neoprimtivism, Cubo Futurism, Rayism, Constructivism and Suprematism among them.

Russian Avant-Garde Artists

Jane Sharp points out that the rapid succession of ‘isms’ in the preceding years had generated an intense ‘anxiety of anticipation’ among Russian artists. Nina Gourianova states that there was no unity within these movements apart from a desire for freedom of artistic conscience – to not be bound by any pragmatic, political, social or aesthetic goals. Artists wanted to consciously expand artistic space by deconstructing canonical aesthetic ideals. The emancipation of any artistic form from any automatic association with a preconceived meaning created conditions of possibility for Russian artists to abandon reference to the world of objects all together and to articulate some of the earliest and most confident abstract works in poetry, painting and illustrated books and music.

From 1915 on, the Russian avant-garde was marked by multiple approaches, which rooted mainly in two opposing ideas on artistic practice by Suprematist Malevich and constructivist Tatlin, the two protagonists within this essay. The extent to which abstract art can be considered apolitical is dependent on various factors, including the artist’s intentions, the historical context, and the viewer’s interpretations.

Abstract art within Russia was not produced within a vacuum, formed from ‘surges of inspiration,’ despite what the writings of Malevich or Kandinsky may lead us to believe. Within the various movements that embodied abstraction as their mode of expressions, references to the past, present and the future were profound, both through what they produced and what they did not. The emancipation of any artistic form from any automatic association with a preconceived meaning created conditions of possibility for Russian artists to abandon reference to the world of objects all together and to articulate some of the earliest and most confident abstract works in poetry, painting and illustrated books and music.

Russian Abstract Art and Eurocentricism

Russian avant-garde abstraction turned away from Eurocentric values established by two centuries of encroaching Westernisation and towards the cautious revision of the beginnings of Russian religious and intellectual thought, shaped by Byzantine and Eastern philosophies and embedded in pre-Petrine culture. There was a sharp pronounced break with previous European cultural traditions in an attempt to create a new self-identity, to distinguish the ideology of the Russian avant-garde from that of earlier ‘Westernised modernist movements.’

Nikolai Berdayev wrote: “We are witnessing a general crisis in art that is shaking it to its thousand-year foundations. The old idea of classical beauty has dimmed forever, and one sense that there is no returning to its images. Art is convulsively trying to escape from its boundaries.” This ‘crisis’ has been understood in literature surrounding, and during, the avant-garde as anarchic. The term anarchy in art has acquired a more abstract significance that is not entirely bound to social or political spheres, but to the major explorations within the pre-war Russian avant-garde.

The artists that were intent on creating their own narrative and history used terms such as anarchy, destruction and anarchic messages in their work to valorize the new aesthetic system, namely Malevich, Kandsinky, Stepanova and Goncharova.

Goncharova, Cats, 1913

Goncharova, Cats, 1913Varvara Stepanova reflected on the direction that Russian art had taken in her diaries: “Russian painting is as anarchic in its principles as Russia in her spiritual movement. We don’t have stylistic schools and every artist is a creator, everyone is original and radically individualistic.’ There was a desire to create life, to construct forms out of nothing and to attain ‘nonobjective creation.’ This anarchic approach to the destruction of preexisting styles and theory substantiates the claim that abstract art was inherently apolitical, one defined by the artist.

However, just because there were no direct links to artists and definitive political factions it does not mean that the entire Russian avant-garde was apolitical. There was a certified engagement with social and political dynamics that Gourianova terms ‘anarcho individualism’ This manifested in a cultural specificity to the art produced in the period that evidences that abstract art, and its means and intent of production, were not exclusively apolitical – revealed in the non-objective works of Tatlin and Malevich. Semantically, Malevich did not use the term ‘abstraction’ in his dialogue, instead ‘non objectivity’ was favoured.

Kazimir Malevich

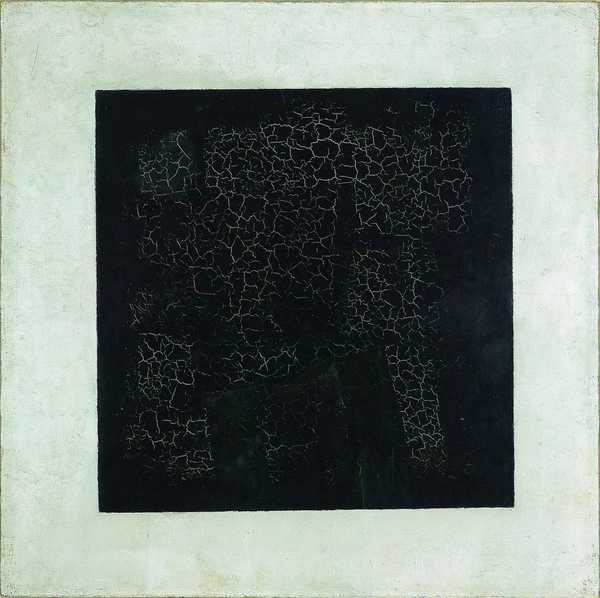

His renowned work ‘Black Square’ a bastion of Suprematism and the entire Russian avant garde movement, drew from a number of preexisting ‘non-objective’ illustrations of a black square, as well as heavily from the Russian iconic tradition. This cultural specificity reveals an engagement with socio-political events and cultural discourse. Despite the radically non-representational manner of Black Square the use of the icon paradoxically presented both Tatlin and Malevich with a uniquely Russian representational ancestor.

Vladimir Tatlin

The interest in iconic representation, revealed in the back of Tatlin’s wooden panels and constructed corners, held together by a shponk, a wooden beam traditionally attached to the back of icons and in the placement and metaphysical power that Black Square held when exhibited at the 0.10 exhibition. Malevich translated it into a more contemporary iconicity – through the corner placement at the 0.10 both the Counter Corner Reliefs and Black Square invoked a specifically Russo Byzantine artistic genealogy. Tatlin and Malevich were keenly aware of the discourse surrounding the Russo Byzantine revival and had mobilised it to advance their own artistic goals. Icons constituted image paradigms that enabled the structuring of space and triggered a range of literary and symbolic meanings and associations in their viewers. This reveals an investment in a broader cultural dialogue that prevents Malevich and Tatlin’s works from exclusively being deemed ‘apolitical.’ As Bowlt noted, ‘such absolute works as Black Square have placed a fatal question mark above the whole development of easel painting, whether representational or not.’ The Black square operated on multiple registers as both an icon and an anti-icon – a secular and a religious object, an act of destruction and simultaneous creation.

Malevich, Black Square, 1917

Malevich, Black Square, 1917Abstract art’s inherent ambiguity and openness to interpretation can be both a strength and a limitation in assessing a broader socio-political message. The political and social ideas of pre-revolutionary Russian avant- garde circles were extremely eclectic, making it nearly impossible to say much about their actual political orientation. Its ambiguity was rooted in its apolitical status and an artistic belief in the value of the resistance of art to narrative, to literature and to figurative realism as it had developed in Russia during the latter part of the 19th Century.

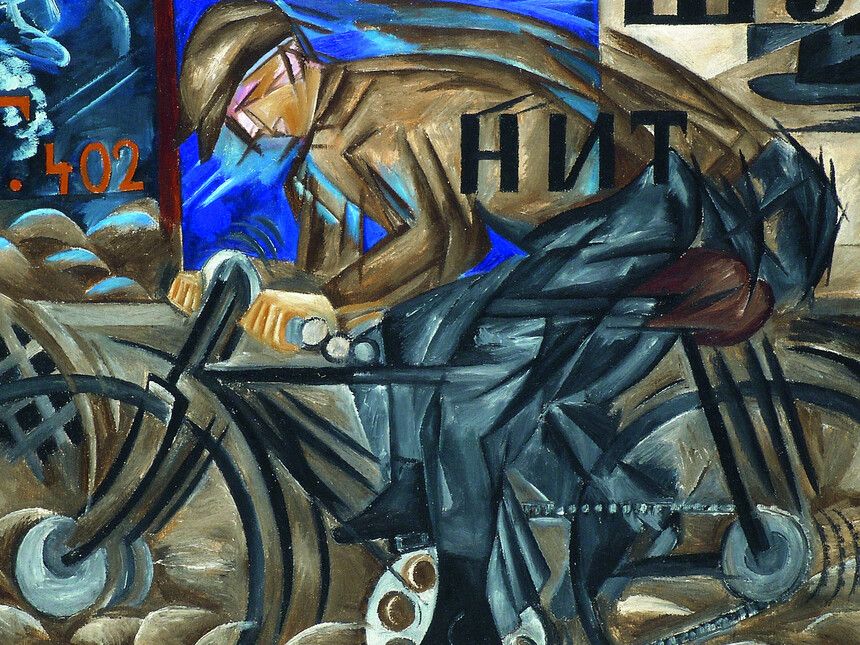

Goncahrova, Cyclists, 1918

Goncahrova, Cyclists, 1918David Burliuk wrote “Today we do have art. Yesterday it was the means, today it has become the end. Painting has begun to pursue only painterly objectives. It has begun to live for itself.” It is clear from the constant insistence on ‘painterly objectives’ as exclusive of representation, that the notion of autonomy itself was conceptually interlocked with that which it set out to negate – figurative realism.

For Malevich’s Suprematist works to be perceived as art required a familiarity with the idea that the system of art was of a geometrical order (an idea that could be traced to the classical tradition) – and that a function of art could be to lay that system bare. Planes, lines and surfaces came to be seen like the verbal ‘material’ of language and to correspond to the devices in language which rendered that material ‘artful.’ The square for Malevich of the line for Rodchenko were both the raw material and a basic device of art.

Symbolism and the Avant Garde

Malevich, Goncharova, and Popova contain geometric configurations, however they do not represent or symbolize geometric shapes by pictorial symbols, rather they display specific cases of rectangles or other geometric shapes, and therefore we cannot claim to honestly understand them beyond the elementary level, as geometric, apolitical, forms. Their views can be summarized as the ‘politics of the unpolitical’ a phenomenon that was formulated by Herbert Read in his critiques of contemporary culture. Abstract, non-objective artists looked for an art that would represent the noumenal and universal world, instead of depicting the phenomenal world by means of representation of the specific objects that are in it, a decidedly apolitical stance.

Individual self-expression as the root of abstract art is often adopted as a romantic approach to the artistic process, the hand of the artist principled. Both Kandinsky and Malevich endeavored to cultivate an image of themselves as a genius, Malevich in particular was obsessed with confirming his status as the first ‘abstract’ or ‘non-objective’ artist – his Black Square acting as his evidence. This affirms the notion that abstract art is shaped by self-expression, and an ultimately apolitical agenda.

Malevich dated the work to 1913 in order to align with the drawing processes of the opera set design that contained a square within a square; he sought to alter the historical record to link the emergence of Suprematism to his earlier work, its actual date of production being two years later. Furthermore, the work was created very much in tandem with the rest of artistic production during the period, he was not an isolated artistic genius. Popova, Larionov, Goncharova, were all artists that had explored the geometric, contentless forms that Malevich stripped even further back.

Mikahail Larionov

Mikahail LarionovIndeed, the set designs reflect an obsession with the square as a form that can be manipulated to suggest and defeat the sense of spatial recession, creating a deliberately incongruous effect of spatial disarticulation. The square acted as a vortex, destroying order. It became a metaphorical incarnation of Malevich, functioning as his principal image in a non-objective universe, signifying his unprecedented genius. Malevich was determined to make himself synonymous with the origins of abstraction, with Black Square as his calling card. What this reveals therefore about the creation of Malevich’s abstract art was that the ‘self’ was incredibly important, far more so than any engagement with socio-political factors.

Conclusion

The artists that pioneered abstraction held the belief that the greatest works of art are those that illuminate us as humans, that reveal something to us that we did not know was possible or tangible. Abstract art did not strive to become political which made it even more powerful, it is of value despite this. It survived through the socio-political mechanisms that were endeavoring to diminish it, to reduce it to a statement or a phase.

The official attitude towards art had been revised – what had been artistically ‘immoral’ yesterday today became conventional, what had been condemned was now extolled. The period from 1910 to 1918 was one of the most profound and influential periods of artistic production that would create an artistic legacy for Russia that it had neglectfully not yet been afforded.